GOOD GERMANS, BAD NAZIS &

UGLY COMMIES

by Ben Pleasants, guest contributor.

[March 24, 2007]

[HollywoodInvestigator.com]

If you've been reading fiction lately, you may be aware of an interesting

phenomenon:

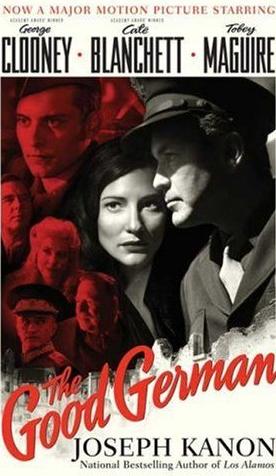

the suspense novel that crosses into literature. Take Joseph Kanon's The

Good German. [HollywoodInvestigator.com]

If you've been reading fiction lately, you may be aware of an interesting

phenomenon:

the suspense novel that crosses into literature. Take Joseph Kanon's The

Good German.

The novel was a hit, although Steven Soderbergh's

film adaptation disappeared at the box office before anyone had a chance

to see it. Yet the film's every bit as good as the book, and the

book is as good as Greene's The

Third Man, Hemingway's The

Sun Also Rises, and LeCarre's Smiley's

People.

You care so much about Kanon's

characters, you don't want to let go. He recreates a place and time

that's been in our consciousness forever, but in an undefined way until

now. Berlin, right after World War II. The

Potsdam Conference.

That's enough for a good Bourne in Berlin, but what makes this literature, not just a Hitchcock thriller,

are the book's moral questions.

Lena Brandt uses her sexuality

to survive Nazis, Stalinists, and Americans. She epitomizes the city

of Berlin post-World War II. Desperate, terrified, yet hopeful.

Renate Naumann is a "greifer"

or "grabber of Jews," who is Jewish herself. She's on trial for betraying

her

people to the SS to save the life of her young son. Soderbergh removed

Renate from the

book, grafting her crimes onto Lena. That made Lena so dark,

it ruined the film.

Jake Geismar, an American,

was Lena's lover before and after the war. He's a Jake

Barnes-like reporter who takes us on a very noir 1940s tour through

postwar Berlin. The city itself is the real star. Kanon is

a master of atmosphere.

Emil Brandt is Lena's chemist

husband. The Americans and Russians both want to recruit Emil, despite

his work in SS concentration camp "experiments." We know the US hired

these

guys, denying their involvement in war crimes.

Kanon brings the conundrum

into focus: Who is the good German?

One is Emil's scientist father,

Professor Brandt, who stayed in Germany but refused to work for National

Socialism. He hates what his son did as a "scientist." Brandt

is dropped from the film, though he's the ethical German, the conscience

who observes politics turning into murder.

Then there's Captain Teitel,

a German-born American Jew who returns to prosecute war criminals while

Congressman Breimer, friend of I.G. Farben, recruits Werner Von Braun's

colleagues.

For those who read history

and like Immanuel

Kant, the book's a treat. But Kant is dropped from the film;

only gray materialism triumphs. Grayer than The

Third Man.

Joseph Kanon prefers to be

called Joe. I told him he'd written a major work of literature, not

just a commercial suspense novel. He thought it was a love story,

both for Berlin, and between Lena and Jake. He was amused at my enthusiasm.

Ben

Pleasants: Considering that you were born after 1946, how

did you bring Berlin to life, street by street, district by district, with

such skill? And might I add, sympathy. "Nobody walks quickly

over rubble."

Joseph Kanon:

I've never lived in Berlin, but I've been there, and sometimes feel as

if I've walked the whole city. The best way of getting to know a

city. Not every place strikes an imaginative resonance, but Berlin

did with me -- parts of it I felt I knew instinctively.

Researching The

Good German presented a challenge because the Berlin of 1945 doesn't

exist. Nearly the entire center was leveled by bombing. Street

names

have changed. But I wanted to write about the Allied Occupation,

and the buildings they used, by definition, had survived the bombing. You can still see where the Control Council met, the headquarters for the

Kommandatura.

Other sources are movies made

at

the time. The

Murderers Are Among Us, Rossellini's Germany

Year Zero, some scenes in Zinnemann's The

Search.

Print sources were valuable. Diaries, letters, journalism, often as interesting for what they omit as

for what they notice. An extraordinary contemporary memoir is A

Woman in Berlin. Popular histories that lean heavily on personal

interviews

(e.g. The

Last Battle) are a good source.

But ultimately, you make the imaginative

leap and put yourself there. Whether you manage this successfully

is for readers to decide.

Ben:

You dedicate the book to your mother. There are interesting and powerful

women in this book. Was your mother influential in bringing any of

them to life?

Joseph:

No, it was simply my mother's turn for a dedication. No German connections. She spent the war years as an American bobbysoxer.

Ben:

Did it bother you that the screenwriter took such liberties with the book? The way he portrayed Lena. And he left out Emil's father, one of

the most interesting and ethical Germans in the book. Was something

lost? For me there was.

Joseph:

The cliché is that every writer wants his book made into a film,

but is disappointed/outraged when changes are made. But a movie isn't

illustrated text. Tully is a case in point. In a book, you

can discuss how a black market operates; in a film you must show it operating. So Tully's alive in the movie.

I admire Soderbergh. He

did extraordinary things with archival footage. The film is a triumph

of the 40's style. The cast was a dream cast.

Some changes seem bewilderingly

arbitrary. Jake now works for The

New Republic -- an unlikely press pass in '45 -- not Collier's. Congressman Breimer represents Schenectady, not Utica. Why? It's possible there was a reason. It's also possible the writer had

simply forgotten and couldn't be bothered to check.

The one change I found difficult

was confalting Lena with Renate, and dropping the love story. To

me, this was the heart of the book. But the book is not the movie.

Ben:

I'd say the point/counterpoint of the novel is the American prosecutor

Bernie Teitel, who seeks war criminals in 1945, against Congressman Breimer,

who seeks scientists for the next war between the US and the USSR. Were you conscious of this tension?

Joseph:

What interests me is the moral gray area of war and its aftermath. It corrupts all, even the well-meaning. On the one hand there is

moral outrage and demand for justice; on the other, the demands of self-interest

and realpolitik. Most characters act somewhere between cynicism and

good intentions. The war begins with Casablanca,

all sharp black and white, but it ends with The

Third Man, a murkier, gray area of moral compromise. The era

that began our own.

Ben:

Lena is fascinating. Did you fall in love with her yourself?

Joseph:

Whenever you do a love story, you should be a little bit in love with the

character.

Ben:

I love the contrast between Professor Brandt and his son, Emil. Brandt

says "They [the Nazis] destroyed Germany. The books, then everything.

It wasn't theirs to destroy. It was mine, too. Where's my Germany

now? Look at it. Gone. Murderers." Lena replies,

"Emil wasn't that." But the professor knows that is not true. He answers, "Be careful when you put on a uniform. It's what you

become."

Joseph:

Brandt is a decent, cultured man who's seen his society hijacked by gangsters

and led to its doom. Worse, he's seen his son become part of that. A tragic moment. But it's also youthful naivete and ambition. Science is young man's game. For all Emil knew, the Nazis might be

in power for his entire lifetime. How does he arrange his life? His work? There is some resonance with Speer,

who seems, according to the memoirs (often disingenuous), to have thought more of his architectural ambitions

than moral issues.

Ben:

Renate's trial has an ironic twist. Her defense lawyer observes "in

1944 it was against German law to hide Jews." The judge responds

"are you suggesting that Fraulein Naumann acted correctly?" Her attorney

replies "I'm suggesting she acted legally." Is that your gray area,

where law and ethics are at war?

Joseph:

When laws are made by thugs, there can be no ethical basis -- only a formal

semblance of ethical order. Judges in Germany were asked to administer

appalling laws. A conundrum for anyone professing belief in the abstract

rule of law. Of course, debating fine hair differences is also a

legal tactic that shows how hopelessly complicated rendering justice in

postwar Germany was.

Ben:

How did you invent Emil Brandt? We know Von Braun was not exactly

clean. Yet he is not the epitome of evil, either. Is Emil in

any way sympathetic to you?

Joseph:

I suppose we'd all like to think we couldn't be Emil -– but couldn't we? He believes in himself, in science. He does not see himself as an

enabler

of evil. With youthful personal ambition, a sense of intellectual

detachment, a weak moral center, Emil's the kind of man who'd go along

and make excuses later. Not unlike most of us. He's not Himmler

or Heyditch, true monsters and ideologues.

Ben:

To me, the book's Gunther Behn is the good German. He's a policeman. He has a Jewish wife. He protects her. You have him say, "You

think I abandoned her? Marthe? She was my wife." Then

he breaks down. This is the gray area of the real world, the world

of choices that are very bad and terrible What did you have in mind

when you created this conflicted, almost Dostoevskian policeman?

Joseph:

Gunther, as a good policeman, is conflicted by the demands of the Third

Reich.

Trapped by them. Technically, he's asked to help murder his own wife. Instead, he hides her. Illegally. He ends up losing his wife

to the Holocaust, and himself to bitter and self-destructive cynicism. Sometimes there are no neat solutions. Gunter tries to do the right

thing for the right reason, but loses himself in the process, overwhelmed

by a history no individual can control.

Ben:

Both Harry Lime [in The

Third Man] and Emil engage in terrible things. Emil in starvation

experiments, Harry selling watered-down penicillin. Isn't this a

case of Darwinian survival of the fittest?

Joseph:

Jake saves Emil for Lena's sake, but also for ours. One side or the

other is going to use his scientific skill. Whatever the moral quandary,

it is better that it be ours. I don't see it as Darwinian, though

the Occupation became complicated and compromised. The good German

is the one useful to us.

Ben:

What were your sources on the Soviets at Potsdam?

Joseph:

The best book is Meeting

At Potsdam. I've read Robert

Conquest and The

Fall of Berlin. Vassily

Grossman is worthwhile. All agree on the appalling behavior of

the Russians once they took the city. The Russian statue is referred

to as the Tomb of the Unknown Looter.

Over 100,000 rapes were reported

in the first weeks. Imagine the full unreported scope. Things

were so barbaric, even the Russian command became alarmed. Of course,

all this was no worse than what the Germans had done in Russia. It

was a particularly nasty war on both sides. One reason Americans

were enthusiastically received was simply because they weren't Russians.

Ben:

How do you keep the plot and characters straight as you move along?

Joseph:

I tend to make up the story as I go along, not follow an outline. I like to have my characters surprise me. One of the pleasures of

writing is feeling the text take on its own momentum.

Ben:

What have German readers said?

Joseph:

The book was well received in Germany. The war and its aftermath

are still living subjects there, endlessly debated and evaluated. I went to Berlin for interviews, and everywhere met enthusiastic readers. Some had been in Berlin at the time and said the book was accurate.

Ben:

Your novel, Alibi,

is also set in the 1940s. Could you compare it to The

Good German?

Joseph:

It's set in postwar Venice. The anti-Berlin, where nothing happened. No bombs were dropped. People sat out the war. Yet the war

had a way of intruding.

For me, The

Good German is the richest and most complicated of my books. But it's all up to the reader to judge

Ben:

It's a great book. Thank you, Joe. This has been a pleasure.

Copyright 2007 by Ben Pleasants.

|