A special

Hollywood Investigator report ... appearing for

the first time anywhere:

WHEN BUKOWSKI WAS A NAZI,

Part 1

by Ben Pleasants, guest contributor.

[April 8, 2003]

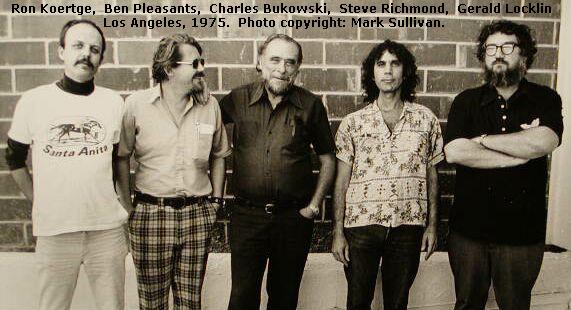

[HollywoodInvestigator.com] The subject of Nazism came up first at Canter's, a famous Jewish restaurant

on Fairfax. Bukowski and I were both working at the LA Free Press

in Hollywood, and we were preparing a symposium on LA Poets including Gerald

Locklin, Steve Richmond, Ron Koertge, and Bukowski, all Wormwood poets. I was to conduct the interview.

"Symposium means with drinks," Bukowski barked at the editor, Penny Grenoble. "Beer in bottles. Pabst Blue Ribbon."

Penny, who had graduated with a PhD. from RPI, agreed. "We'll have

lots of beer in bottles, I promise. And don't worry about your column. You'll get your regular pay. The Symposium will fill the space of Notes

of a Dirty Old Man next week. You'll get paid and you won't have

to

write a thing. Okay, Mr. Bukowski?”

They had a playful relationship, the slender and beautiful editor dressed

in high fashion and still in her twenties, and the fiftyish satyr in down

at

the heel shoes and khaki pants.

Bukowski gave her a mock grimace: "You're not trying to edge me out

now, are you?"

The editor of the Free Press laughed. "You're the mainstay of our

adult pages. How could I do that? And we'll require the usual

Bukowski drawings."

We agreed to conduct the interview on tape. Bukowski suggested the

two of us meet a few days before to go over the ground rules. At

that time he was living on Carlton Way in East Hollywood and I was in Beverly

Hills on South Doheny Drive. When he suggested Canter's, somewhere

in the middle, I told him I didn't much like Jewish food. He said

he found the place entertaining, especially the hefty waitresses in gravy-stained

uniforms marching around with huge trays of roast beef and whipped potatoes.

"They have good pastrami," he said. "And besides, they have a bakery."

He knew I had a weakness for pastry.

We showed up at noon a few days later, both ordering pastrami on rye with

whipped

potatoes and beer. One of the hefty waitresses took our order. It was a hot L.A. day and she was sweating in the heat.

While we were waiting for our food to arrive, Bukowski gawked at the predominantly

Jewish diners, and swigging down a brew, yelled loud enough so all could

hear: "TURN ON THE GAS."

No one looked up. I shook my head and refused to laugh.

On heavy drinking nights at his place in Hollywood, he had often howled

at

the Hollywood Jews and how they had ruined one writer after another, from

Fante to Saroyan to William Faulkner. I agreed with him it was not

a nice business.

The sandwiches on the menus were all named after Hollywood Jews: moguls,

directors, actors, and comedians. One was the Buck Benny. That

was a hot dog, the cheapest meal. I tried to change the subject by

mentioning

the time I saw Jack Benny on Spaulding Drive floating along with that delightful

walk he had.

"Never

mind," said Bukowski, dismissing the subject. He didn't want to talk about

Jack Benny. "If those guys [Hollywood Moguls] did a film about the

garment industry, the bad guys would be Eskimos."

That did make me laugh and spit up my beer. I didn't disagree, but

pointed out that Jack Warner and Louis B. Mayer didn't justify Hitler.

"What do you have against Hitler?" he asked. "Ever read him?"

I told him no, then confessed a little secret: "I'm a quarter Jewish on

my father's side. My grandmother's family come from a little town

east of Frankfurt on the Main River."

Bukowski laughed. "Being a quarter Jewish is like being a quarter crazy;

it only matters if you take it seriously. My parents were both German

Catholics

and I could give a flying fuck about what they believed. It means

nothing. The important thing is who you are. The Beverly Hills

Anarchist."

He always called me that, even after I'd moved from Beverly Hills. We ate

our pastrami on rye, drank our beer and went on planning the symposium.

It came off as planned on October 14, 1975, with bottled beer spiced with

great humor and vulgarity, decorated with Bukowski's delightful illustrations

and a few amusing photographs.

A few weeks later I suggested to Bukowski that I might want to write his

biography. That was probably the biggest mistake I ever made in my

life:

Getting the facts from a writer of fiction is about as easy as curing herpes,

but as time went by, Henry Charles Bukowski Jr. began to open up the Pandora's

box of his life, Nazis and all.

This is what he told me.

* Young Outcast

From the

time

he was a small boy, Bukowski was super-conscious of being German. He was

an only child whose parents spoke German late into the night as

he slept

in his room next door. At the dinner table, when they didn't want him to

know what they were saying, his parents would "turn on the Deutsch." It was all around him. His grandfather, Leonard Bukowski, and his

grandmother Emile (they were divorced and lived separately), both spoke

German when they came to the house for Christmas.

Leonard, who was from Prussia and had fought in the Franco-Prussian War,

was also a heavy drinker. "When he got drunk," his grandson recalled, "he

would sing old German war songs and put on his war medals."

Then there was Bukowski's mother. He described her as "the prettiest

girl in Andernach." When she received letters from her parents and

brother back home, she would read them over and over, missing her family. This would occasionally annoy her husband, who would shout at his wife:

"You think you're so great because your brother is the Burgermiester of

Andernach." (That proved false, as Heinrich Fett told me himself

when I met him in 1977).

When he

was little, Charles Bukowski was a momma's boy, coddled by his mother;

what irked him most was the intimate conversations his parents had late

at night in a language he could not understand. Henry Sr. was fluent

in German while Henry Jr. could not speak a word of it.

Sometimes, when Katherine was especially lonely and craved German company,

Henry Sr. would take her to the local German meeting place, the Deutsche

Haus,

located at 634 15th Street, close to their home. Here, when he had

a little money, he would treat his wife to a meal, buy her a German magazine,

listen to a German band, or watch a travelogue on what was going

on in Berlin. If they came for lunch on a Sunday after church, Henry

was dragged along, but the long hours of watching people speaking a language

he did not understand, bored him.

Bukowski was always very touchy when people asked him why he had not learned

German. He said his parents discouraged it; they wanted him to speak

perfect English.

He said that after World War One, German was not taught in most public

schools; but both L.A. High School and Los Angeles Community College offered

German.

Bukowski always resented the fact that his father could read and write

German, and when I asked if that's why they kept him on in Coblenz after

the war, he got angry and said, "No. He was only a typist."

Whatever attitude his parents had toward their son learning German, they

did expose him to the Deutsche Haus, a little island of German culture

in a sea of American white bread. There Bukowski discovered German

music,

German films, German food, and German books and magazines, some written

in English. It was there he first observed the German-American Bund

in full uniform. His parents even took him on an outing to Hindenburg

Park in La Crescenta where he celebrated Hitler's birthday with a torchlight

parade. It was the year of the 1936 Olympics.

At his most forgiving, he would say of his parents, "Living in that house

I never learned German except for the songs."

What brought

Bukowski around to the Nazi viewpoint, and more particularly to the ideas

of Adolph Hitler, is hard to say. It began in the depth of his solipsism,

at the time of puberty when his skin erupted and in the eyes of many he

became a monster. Though he says over and over that he was some kind

of leader among the friends he had, their own words betray him as an outcast

and a loner. Girls feared him; teachers taunted him, his fellow students

would talk about him behind his back.

This taught him the lesson of the gifted misanthrope: writing can be the

avenging sword. All the bitterness that welled up in him as he broke

out in boils and huge, exploding pimples, became the fuel that drove his

writing. He looked for writers with similar views and found Celine,

Ezra Pound, Jeffers, Hamsun, and Adolph Hitler.

Nazis loved outcasts. Nazis loved vengeance. Nazis always blamed

their problems on someone else! This pattern repeats itself through

Bukowski's whole life. Here's an example from Mount Vernon High School.

Bukowski told me he had a gym teacher named Wagner who had it in for him:

"My friend Mullinax and I were always in trouble over little things. We were put on the garbage can crew. I forget where we were carrying

them. I guess where they got loaded. There was a place where

the trucks would pick them up. We had to go around carrying these

garbage cans to the loading area. And pick up little pieces of paper

with a sharp stick. It was small things, but we were always on the

outs.

"Especially

with this guy Wagner, the gym guy. He was always on us and we would

have to stay after school. We did nothing, really. We were

just outcasts. We felt it. We didn't have it; they landed on

us. I remember one time I had to stay after school and rake out the

sawdust pit. You get stuff that's fallen in. I made all kinds

of money. I got dimes and nickels. The money looked good. It always did. I remember that was interesting getting all that free

money from raking up the sawdust pit.

"Then,

on Graduation Day, I was standing on line with my friend Baldy and this

guy Arnold Woodchurch and his buddy, who had the longest cock in school. I forget his name. He was always in trouble because the girls were

after him. Anyway, Wagner came up to us in the graduation line and

he walked over to me and said: 'Listen, you guys are graduating. You think you can get away from me, but I'm gonna get you! You can't

get away from me.' This guy was crazy."

When I played back the tape for William "Baldy" Mullinax, he replied: "One

or two times it happened. That's what he remembers from Mount Vernon?" Mullinax recalled the first dance he ever attended, his first girlfriend,

his growing interest in science, while Henry Charles Bukowski Jr. could

only recall his humiliations, his battles against authority, his struggles:

In Hitler's phrase, Mein

Kampf.

Bukowski's one triumph of childhood was his essay on President Hoover and

the L.A. Olympics, though Bukowski had to admit to his teacher, it was

a fiction; he hadn't attended. And then there was the walk he took

from home all the way to the beach with Eugene Fife, who would later become

a Commander in the US Navy.

School for Bukowski was always torture. Later, speaking of poetry,

he told me his one great mission was to "get the bullshit out of it; the

stuff about learning." To Bukowski teaching was a dishonest profession

and those who were scholars were phonies!

Life on the page was about three things: the battle for position, money,

and sex. Out there in the arena of life those were the three things

that mattered.

When I came back with Baldy's corrections, Bukowski got angry and curt

and commanding: "Go find Arnold Woodchurch," he said. "Woodchurch

was laying all the girls. He was doing a lot of fucking and the guy

with the big cock was doing a lot of fucking. I wasn't and Baldy

wasn't. Baldy's pathetic."

Much of Bukowski's high school career in his words and others have been

carefully altered to conceal his humiliations, failures, and loneliness.

The myth that his father forced him to attend Los Angeles High School is

just that: a myth. Bukowski lived walking distance from campus and

was assigned to L.A. High along with his companions, Jim Haddox, Bob Stoner,

Ray Shuwarge, Bill Cobun, Hal Ortner, and Bill Mullinax.

On paper Bukowski was a bright student. He tested well, especially

in language and mathematics, and his father had high hopes that his son

would find his way in the one of the professions. Henry Sr. felt

his son's abilities lay in technology, science, and engineering.

He thought that if he applied himself and kept up with his homework, Henry

Jr. might make it into a good college and become the "success" he was not.

But his son had other ideas.

"My course," Bukowski told me "was mixed up. My father wanted me

to be an engineer. I was taking drafting and Spanish and all.

I ended up in a vocational program because I couldn't pass Spanish and

I didn't like drafting. My father just gave up and said, 'Okay, give

it up.' So I took whatever was easiest. My mother just went

along."

Oddly, when I read Hitler's Mein

Kampf upon Bukowski's request, I came to the following passage:

"My father forbade me to entertain any hope of ever becoming a painter. I went one step farther by declaring that under those circumstances I no

longer wished to study. Naturally, as the result of such declarations,

I got the worst of it and now the old man relentlessly began to enforce

his authority. I remained silent and turned my threats into action. I was certain that, as soon as my father saw my lack of progress in school,

he would let me seek the happiness of which I was dreaming. I do

not know if this reasoning was sound. One thing was certain: my apparent

failure

in school. I learned what I liked, but above all I learned what in

my opinion might be necessary to me in my future career as a painter. In this connection, I sabotaged all that which seemed unimportant or that

which no longer attracted me."

[p.14

of the 1940 Reynal & Hitchcock edition]

I pointed the passage out to Bukowski. "Yeah, I know," he said.

With little homework and no interest in team sports, no job, no clubs,

few friends, and only his chores--which included taking out the garbage,

going to the store, and mowing the lawn once a week--Bukowski had his afternoons

free. These he spent alone at the library at La Brea and Adams, or

as a hanger-on with Baldy, Ray Shumarge, and Jim

Haddox.

Bill Mullinax, who he describes as pathetic in all his poems, stories and

in Ham

on Rye, his childhood novel, was really the popular one. Both

Mullinax and Haddox were in the ROTC Officer's Club by their Junior Year.

Mullinax had various girlfriends including Marla Morton, who wrote him:

"To more and better astounding stories." Lonetha Davidis congratulated

him on his skills in chemistry. Hal Ortner called him his "bosom

pal," while Bob Stoner congratulated him on his success in ROTC and Elaine

Lettice consoled him as a "fellow-sufferer in Geometry." A girl named

Betty wrote: "To a boy who tried to change me and did." She left

her telephone number. Ray Shuwarge wrote: "Be sure and don't join

the navy as you have a good future in the medical field, and I wouldn't

like to see our trio (Lobdell, Ray, Bill) broken up."

There's no mention

of Henry Bukowski, who did not take chemistry or geometry, did not join

Buildings and Grounds along with Mullinax, Haddox, and Shuwarge, and ran

away from girls.

Bukowski did nose around the newspaper, The Blue and White Daily, but disliked

the editors: Matthew Rapf, editor; Morton Cahn, managing editor; sports

editor Melvin Durslag; and news editor Robert Weil.

He told me he read the Examiner at the time because William Randolph Hearst

published Hitler and Mussolini, though he fired Hitler because he missed

his deadlines!

One student he did single out, but not as a friend, was Harold Mortenson,

treasurer of the Senior Class. "I knew an honor student," he told

me. "He got straight A's. His name was Mortenson. I forget

his first name. He was a straight A student and he was an idiot.

I mean he was just dumb. All he did was study the books for tests.

He'd spit on his hands and wipe it in his hair. He didn't have women

either."

In Ham

on Rye he's Abe Mortenson to make him Jewish. He's the one Bukowski

runs into in a baseball game and his mother fears he'll sue them.

"She'll get a Jewish lawyer. They'll take everything we have." (Chapter

42, p. 185)

He had even more fun with Jim

Haddox, who is Jim Hatcher. Haddox lived at 1782 W. 22nd Street

with his mother, Nina Ruth Haddox, who Bukowski described as "café

society." She becomes the grotesque sex object in chapter 38, Claire,

the barmaid, whose husband had committed suicide. The real story,

the one Bukowski held back, is far more interesting, more tragic and ironic.

It appears in the course of this narrative.

When Bukowski reached his eighteenth birthday on August 16, 1938, he was

heading into his senior year with serious problems. Publicly he showed

interest in military service and wrote in Baldy's yearbook: "Best wishes

to a good army man. I hope you will be a Nevins' sergeant next term.

NAVY. Hank Bukowski. 1st Class Seaman."

John Nevis was the Captain of Company B, Mullinax's company, while Jim

Haddox was in Company C, serving under Captain Maynard R. Chance, and Bukowski

was in Company A under the command of Captain Harcourt Hervey Jr. Privately, as Germany gobbled up the Sudetenland and moved into Austria,

Henry Jr. cheered Germany on to war in Europe.

All this came to a head in the summer of 1938, when he had to prove his

citizenship. Was he German or American? On August 1, 1938,

he wrote to the U.S. State Department requesting a record of his birth

in Andernach through the offices of the US military. On August 9,

the division chief of the Foreign Service Administration wrote back:

My Dear Mr. Bukowski:

In accordance

with the request contained in your letter of August 1, 1938, I am pleased

to enclose a certified copy of the Report of Birth of Henry Charles Bukowski,

who was born August 16, 1920, at Andernach, Germany.

His

final year in school was not memorable to him, though he did give me some

insights into his mindset in June of 1939.

"L.A. High School was a rich man's school at the time. They all had

sports cars. We walked or rode bicycles. They came from huge

distances just to attend this special school. The women wouldn't

pay any attention to you. The other guys got the girls. We

were the outcasts. I didn't allow myself to like girls. The

report cards were very important to my parents. They were always

disappointed. It was not so bad. I had mostly C's and a couple

D's."

But

in typical Bukowski fashion, he did recall one bit of zaniness:

"This

one time there was a teacher in high school. I was making good grades

and I was passing her tests. It was the next to the last day before

report cards.

"She

said, 'Henry, I'm going to flunk you.'

"I said,

'Why?'

"'I'm

going to, that's all.'

"Strange,

I thought. She must be in love with me. She wanted me to stay

in high school. See me another term. She was an old thing. That was my only thought. I felt the hate, like she didn't want me

to go, but I also felt the love. That was the first time I felt somebody

really cared about me."

I

looked for that wrinkled smile of his when he was being ironic, but I could

see he was dead serious. I asked for the teacher's name. He

couldn't recall it. It all seemed so pathetic: MACHO BUKOWSKI, the

Hemingway warrior, and here he was telling me this old lady was the first

person who ever loved him.

I asked if she carried out her threat and flunked him.

"No," he said. "My mother found out. She went over there and

cried and cried for hours. So she gave in. It was so strange. I was getting passing grades and she wanted me to stay."

I had to laugh. "So you were saved by your mother!"

He nodded. "It wasn't the last time, either," he said.

Though he remembered in detail this crazy, deranged event, he could hardly

recall his graduation from high school. "They played Wagner," he

said. "I went up and got my diploma. This gets sadder and sadder. I'm about to weep. I should have been traveling with Stravinsky's

grandson

and going to operas."

In Ham

on Rye, Bukowski mourns the state of his lonely life as he watches

through the windows as the senior class enjoys their prom. He neglects

to mention that Bill Mullinax, Jim Haddox, Bob Stoner, and most of the

friends he knew in ROTC were all at the dance, and that all of them would

be in the military before Pearl Harbor.

After describing Jimmy Hatcher (Jim Haddox) as "soft and standard" in Ham

on Rye (p. 160), and telling him to his face "I don't like anything

about you," he lines up the rest of his acquaintances for fictional assassination

as they dance at the prom:

"I hated them. I hated their beauty and their uncontrolled youth…"

While Jim Haddox went directly into the Army Air Corps, Bill Mullinax was

preparing himself for a career in engineering at LACC, while Henry Charles

Bukowski Jr. remained in the same bedroom he'd been since childhood, drinking,

nursing

his anger, without a job, afraid to be seen with women, waiting for that

blinding light that would propel him forward into greatness.

His epiphany came on September 1, 1939, as the armies of Adolph Hitler

marched into Poland, dividing it up with their new partners in crime, the

USSR.

This is the end of Part One. Go to Part

Two, Part Three.

Copyright 2003 by Ben Pleasants.

|