A special

Hollywood Investigator report ... appearing for

the first time anywhere:

WHEN BUKOWSKI WAS A NAZI,

Part 3

by Ben Pleasants, guest contributor.

[April 8, 2003]

[HollywoodInvestigator.com] He worked as a stock clerk, a sorter in a dog biscuit factory, a packer

in an auto parts store. Again, no security checks. Those types

of jobs were going begging as half the men in America were in the service

and the other half were working in defense plants; women too! Lugging

his typewriter from city to city, still hating the government and hoping

the Nazis would win the war, Bukowski had found a crack in the universe

where he could crawl in safely and write.

He said of his short stories during that time: "They were full of complaints. I wanted too much too fast, and I was weeping in the wind. The unrecognized

artist shit. THE WORLD SHOULD KNOW THAT I HAVE THIS GIFT! I

wrote a lot of that out of me then."

His early stories he sent to Harpers, The

Atlantic Monthly, and Story with a SASE addressed to Longwood...

He returned to Los Angeles in early 1942 to pick up his mail, check on

his friends, and see if the FBI had been looking for him. To his

delight they were not. He was a small fish in a big ocean. His friends were all in the service. Jim

Haddox was training as a pilot; Baldy Mullinax was in the Navy along

with Eugene Fife who was a naval officer. Harold Mortenson Bukowski

had no interest in finding, but he was in college getting all "A's."

So back and forth across the country Henry Charles Bukowski went.

"When I was absolutely broke," he said, "I'd come home. My parents

would put me up. I still had my bedroom. They'd bill me for

food and lodgings, which I had to pay when I got a job."

Mr. and Mrs. Bukowski became more and more impatient with their son. What was wrong with Henry they wondered? Why did he not enlist in

the service? Was he sick or unbalanced or simply a coward?

His mother must have felt some sympathy, with a family on the other side

of the world and her former country at war. Her brother, Heinrich

Fett, would later be appointed head of the Volkssturm for the Third Reich

in Andernach, local commander, but that was toward the end of the war when

Germany would welcome the Americans (they hoped). They needed a man

who knew them and could speak English...

With no letters from the FBI, Bukowski had no intention of enlisting; his

loyalties were elsewhere. In 1942 he read D.H. Lawrence's short story,

"The Prussian Officer," and that helped him write. He had found his

subject: "Ultimate human cruelty. It could have been anybody," he

told me. "It happened to be the Prussian officer. The way he

did it was sooo very good. There's a tightness of line there."

Bukowski loved the story and he loved what it said: human beings are vicious

animals. He went looking for his own Prussian officer and found it

in his namesake, Henry Charles Bukowski, Sr.

In later years, Bukowski would blame his father for everything that went

wrong in his early life: he was a brute, a philanderer, a child beater,

a cheat and a liar; he could not hold a job. He sent his son to a

school where rich boys teased him; he took poor care of his mother when

she was ill and did not appreciate his son's great gifts: "My father

was standard American type. Dull, holding a job, showing up to work

on time."

For the purpose of fiction, and as a vengeance upon him for eternity, Bukowski

turned his father into the Prussian officer. His Uncle Heinrich Fett

had very warm things to say about Henry Charles Bukowski, Sr. when I met

him in 1977, things Bukowski did not want to hear.

Bukowski told me on tape he only got to write what he really felt after

his father died. "When I could get out all the poison." Much

of Bukowski's poems, stories, and novels are all about getting out the

poison. "It saved me from madness," he said. It also saved

him from World War Two!

When Bukowski was arrested by the FBI seems to be a problem. In his

biography, Howard Sounes says he was arrested on a July evening in 1944.

Sounes got the month right but not the year. On July 7, 1942 the

FBI and the Justice Department launched an all-out push on members of the

German-American Bund, including Hermann Schwinn. Bukowski was caught

in that net and taken to federal prison.

Here is

what he told me about his adventures in Moyamensing. Verbatim.

Pleasants: You

had one big-timer in jail when you were a draft dodger.

Bukowski: Oh, Moyamensing. Yeah, seventeen days.

P: That was when?

B: Hell, I don't know. It must have been...

P: 1944?

B: Uh-uh. Much earlier. 1942.

P: I'll have to research

that.

B: Moyamensing. You

think they'll still have the records? Henry Charles Bukowski, Jr.

P: You'll be in there. They'll have your photo and everything.

B: It was quite nice after

a while. You've read it. I won all the money with the craps. Food. After lights out. Better food than I ever ate on the

outside. It's real ancient. When they take you in it's like

a castle. These great big gates. They must be sixty feet high. They open just for you as you go inside. I made more money in there

than I ever made on the outside. I almost hated to leave when they

let me go.

P: You were in there on

draft evasion. Right?

B: I guess that's what they

called it.

P: Did you go to court?

B: No.

P: Did you have a lawyer?

B: No.

P: You just went in there?

B: They figured I was nuts. What they did... they made me go to the draft induction center. They

said, if you make the draft, if they draft you, okay, you're in. If they don't draft you, we'll let you go. I said okay I'll go along

with that. But I couldn't get past the psychiatrist's three questions.

P: What were the three questions?

B: To begin with, they raided

my room after I was gone. They found all these writings. These

mad, garbled writings. So eventually, the psychiatrist had read these

ahead of time.

P: Your short stories.

B: Yeah (laughs). My short stories. Jesus. So I sat down and he said, "Do

you believe in the war?"

I said, "No."

"Are you willing to go to the war?"

I said,

"Yes."

"By the

way, we're having a party next Wednesday at my place. Artists, writers,

intellectuals, doctors. All kinds of interesting people. I

know you're an intelligent man and I'd like you to come to my party. Will you come to my party?"

I said, "No."

"All right, you can go." I looked at

him. He said, "You don’t have to go to the

war. You didn't think we'd understand, did you?"

I said,

"No."

That was all. Pass on through. That was after jail, except I had to wait for a ride back to jail to be

signed out. There were a whole bunch of us sitting there. Hours

went by. I just got up and I walked out of the doorway. I just

walked out into the daylight.

The

fact that Bukowski remembers specifically it was NOT 1944, but much earlier,

he says 1942, is important. It means from that time on he could travel

where he wanted with an UNFIT FOR SERVICE draft rating and not worry about

the FBI any more. The writings they took from him they kept; they

were his Nazi ravings coming off his reading of Mein

Kampf, his experiences in the German-American Bund, his participation

in the America First Movement and his hatred of Hollywood. All three,

much to my amazement, would appear in his work later in life.

On December 11, 1943 his friend Jim

Haddox was shot down over Emden, Germany. He and all of his crew

but one perished. He had made pilot and was a First Lieutenant of

the 100th Bomber Group, 351st squadron, training in Thorpe Abbots, East

Anglia. He left only his mother, Nina Ruth Haddox, who Bukowski described

as a barmaid and an oversexed temptress.

Baldy later said of Haddox, "He was a real war hero. A damned decent

guy." Peggy Harford, who worked with me on the drama desk at the

L.A. Times and graduated with Ray Bradbury from LAHS a year before Bukowski, said she could not remember Bukowski

at all, but she did recall Jim Haddox as "gracious and brave."

Bukowski never mentioned Haddox's war record. To him, Haddox was

the standard American, a hanger-on who followed the great writer around

because "I always draw the weak instead of the strong." He hated

Haddox because he worked hard, was liked by the girls and bombed the Fatherland.

In 1943, with the

draft board off his back, he sat at his typer and the stories rolled out

week after week. "I just pushed them along, four or five a week,"

he told me. "And I didn't keep carbons."

Still

roaming from city to city, he sent on his manuscripts to Harpers, The Atlantic

and Story. Every short story he ever sent to Harpers and The Atlantic

came back with the usual form rejection, but Story was different. Story had published John Fante and Hemingway and William Saroyan. Story showed interest in his work.

For the first time in his life Bukowski was thrilled about writing:

"Whit

Burnett (the editor) always sent me a hand-written note. They were

fairly short. He'd say, 'Send more.' He kept saying it. He'd say, 'Hell, this one is very, very close.' I think he meant

it. There was an awful lot of competition at that time. He

was the only one who cared!"

After Bukowski hocked his typewriter and hand-printed his fiction, Whit

Burnett continued to read him and write back. "Story was the only

one who responded," Bukowski said in animated tones. "The others, Atlantic and Harpers, must have thought, 'Here's

that nut again who prints his own stuff.' "

Finally, in their March/April 1944 issue, Story published "Aftermath Of

A Lengthy Rejection Slip" in the end papers of the magazine. Bukowski

was disappointed. The piece shows wit and brilliance, and he was

approached by an agent who wanted to represent him; but there is something

else all his biographers have left out: the bio he wrote describing his

life:

"CHARLES

BUKOWSKI was born in Andernach, Germany in 1920. His father was California

born, of POLISH parentage, and served in the American Army of Occupation

in the Rhineland where he met his mother. He was brought to America

at the age of two. He attended LACC for a couple of years and in

the two and one-half years since has been a clerk in the post office, a

stockroom boy for Sears Roebuck, a truck-loader nights at a bakery. He is now working as a package wrapper and box filler in the cellar of

a ladies sportswear shop."

Three things jump out at the reader: the fact that he mentions his German

birth; the lie about his father's POLISH parentage; and the change of name.

If Sounes is correct with his dates, the story that Bukowski changed his

name in 1944 from Henry to Charles because he hated his father is as much

a lie as the comment about his father's Polish parentage. He changed

it because he knew the war was still on and his draft board was out there

trying to contact Henry Charles Bukowski, Jr. about his 1A status.

If Bukowski's dates are correct, it's more than likely he did it to protect

his father's job.

Whichever way it went, he published no more work during World War II under

any name.

When I asked him where he was when World War II was over, he said, "I can't

remember. Really. It didn't mean anything to me. It wasn't

important."

I told him even I remembered the end of World War II, VJ Day. My

parents set off Roman candles. I was five. He just laughed

uncomfortably. When I showed him the bio lines in Story about his

father being Polish, he looked back sheepishly and said, "You got me."

My view about Bukowski's fascination with Nazism at the time was simply

one of youthful rebellion; his desire to shock. That's what I believed

at the time. That's what I wanted to believe. My view about Bukowski's fascination with Nazism at the time was simply

one of youthful rebellion; his desire to shock. That's what I believed

at the time. That's what I wanted to believe.

Sometime after the Symposium, when we were returning from Santa Anita in

his little blue Volkswagen, I began to have different thoughts. Bukowski

liked to drive, but he had the habit of avoiding the freeways when he could. "Too many DUIs," he told me.

On our way back, he took a little detour to Hollywood proper and stopped

the car. There were two teenagers in uniforms, one male and one female,

blonde and attractive, looking almost like Brownies until I saw the armband. It was a swastika. They were Nazis.

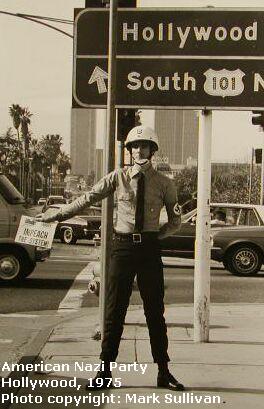

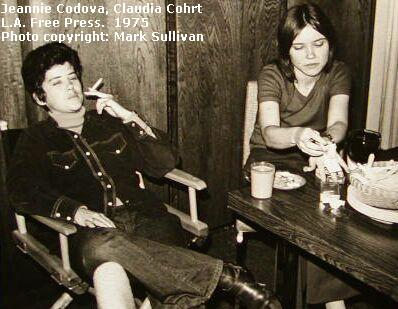

Jeannie Codova, a reporter for the FREEP, had been doing articles for weeks

on all the organizations that were beyond the limits of good taste in politics,

but protected by the First Amendment: The KKK, Jewish

Defense League, Black Panthers,

and the American Nazi Party.

There they were in all their glory. Nazis collecting for their party. I turned to Bukowski laughing. What a joke, but he had tears in his

eyes. I shook my head in disbelief. "See those two? That

could have been me," he said. Then he started up the car and drove

off.

I shook my head. I was beginning to wonder if writing his bio was

the right thing for me. I'd recently bought him a hard to find Celine

novel: Nord. He loved Celine. Nord was about Celine's flight from France after the Nazi defeat. I shook my head. I was beginning to wonder if writing his bio was

the right thing for me. I'd recently bought him a hard to find Celine

novel: Nord. He loved Celine. Nord was about Celine's flight from France after the Nazi defeat.

"Maybe YOU should write a novel about it," I said.

"About what?"

"Being a Nazi."

"You write it," he said. "But make it funnier."

For years and years I thought about doing it, and then I did.

* Jewish Roots

My

next adventure with Bukowski and the Germans was in his own town of Andernach. In 1977, the Los Angeles Unified School District gave me a sabbatical leave,

and with my marriage falling apart I decided to spend it in France: Paris

and Grenoble. Those six months of my life were probably the happiest

time I ever had.

Bukowski wrote me and he made a simple request: He asked me to go to Andernach,

his birthplace, to see if an uncle of his was still alive. "His name

is Heinrich Fett," he said. "He wrote me for a while until I sent

him a copy of Notes

of a Dirty Old Man in German. Then nothing. You'll probably

find him in the graveyard."

In March 1977, I managed to get to Andernach. I did find his Uncle

Heinrich. He was very much alive, delighted to see me, and looking

forward to meeting his nephew. He took me to the graveyard and pointed

out all Henry Charles Bukowski, Jr.'s relatives in Andernach. One

name stood out: Bukowski's maternal grandmother. I looked at the

stone and rubbed my eyes. Pointing to the gravestone, I asked the

old man: "Are you sure THAT stone there is part of his family?”

Heinrich spoke very good English. He'd learned much of it from Henry

Charles Bukowski, Sr. "Yes," not "Yah," he said. "That is the

stone of my family and my sister's family and Henry. My mother."

The name was ISRAEL. I didn't have the courage to ask if she was

Jewish.

Upon my return, when I saw Bukowski, I showed him pictures of the graveyard

and I pointed to the stone.

"Buk, that's your mother's mother. It has to be Jewish.”

He didn't answer. His face grew grim and he changed the subject.

Many years later a member of the Fett family confirmed that Bukowski's

grandmother was named Nannette Israel. Andernach is on the French

border and has many French-speaking people, so that would explain the Nannette. "The Nazis investigated and found nothing," said Heinrich Fett's nephew. "But who knows?"

A few years later when Bukowski and I attended a reading given by Lawrence

Ferlinghetti at Occidental College, a fan rushed up to Bukowski and said,

"All that suffering. So much pain in your work. You must be

Jewish."

"Not a drop," said Bukowski. "Not a drop."

By Jewish law, if Bukowski's grandmother was Jewish, his mother was Jewish

and so was he. The idea that he could betray Hitler by being Jewish

was too much for him to bear.

What Bukowski really wanted to be was the most famous Nazi writer in the

world!

In 1978, when Bukowski returned to Germany, he insisted on singing the

forbidden German anthem, "Deutschland Uber Alles," and wrote about it proudly

in his book Shakespeare

Never Did This. In Ham

on Rye he referred to Harold Mortenson as "just a fool," and to Jim

Hatcher (Haddox) as "a betrayer." When Chinaski breaks Mortenson's

arm in a sandlot baseball game (he doesn't even change the last name, though

Abe is more Jewish than Harold) Chinaski's mother is afraid a Jewish lawyer

will take everything they have. He says of his father, "He was proud

of his son who could break somebody's arm." This adds to the brutality

and viciousness Bukowski would heap on his father.

On the first page of his novel Hollywood,

Bukowski gets back at all those old movies he hated and all the old Jews

who produced them:

"There we were down at the harbor, driving past the boats. Most of

them were sailboats and people were fiddling about on deck. They

were dressed in their special sailing clothes: caps, dark shades. Somehow, most of them had apparently escaped the daily grind of living. Such were the rewards of the Chosen in the land of the free. After

a fashion, those people looked silly to me. And, of course, I was

not even in their thoughts."

The Chosen, Jews in America, MOST OF THEM, did not work. That's what

Bukowski thought. They got money through deals and false promises

and schemes. That's what the whole book is about. It's right

out of Mein

Kampf.

The last time I saw Bukowski was at the track at Hollywood Park. I took my girlfriend, Marlene Sinderman, and introduced her to Bukowski. I wanted to tell him she had met John Fante, was also a diabetic and John

had been fond of her; but before I could open my mouth Bukowski drew me

aside and said, "Get rid of that one. Too Jewish!" I never

told her what he said.

At the end of his life, when they buried him a Buddhist, was Charles Bukowski

still a Nazi or an anti-Semite or both? I'm not sure. I didn't

know him then.

My four great heroes through history have been Spinosa, a lapsed Jew who

preached reason and was ex-communicated by the Jews of Amsterdam; Edmund

Husserl, a Jew who converted to Lutheranism in order to invent Phenomenology

and was kept from the university library by the man he mentored, Martin

Heidegger; Hannah Arendt, author of Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, Heidegger's lover,

and a philosopher of great merit in her own right, loathed by many Jews;

and Mary McCarthy, Arendt's best friend,

the great novelist and critic who hid the fact she was one-quarter Jewish

until half her lovers were Jews.

Add to this my own quarrels with Art Seidenbaum, book editor at the L.A.

Times, over censorship of Noam Chomsky's book on the Palestinians, Fateful

Triangle: The United States, Israel, and the Palestinians; Bill Mullinax's

protestations about Bukowski's "setting me up with lies;" Bukowski's ratcheting

up his rage in print on the friends who disputed his memory lapses; and

it's easy to see how I put off writing about this for almost thirty years.

But an understanding of Bukowski's Nazi loyalties is key to everything

he ever wrote.

Maybe

he was right when he said, "Being a quarter Jewish is like being a quarter

crazy. It only matters if you take it seriously."

I doubt he ever did.

This is the end of Part Three. Go to Part

One, Part Two.

Copyright 2003 by Ben Pleasants.

|