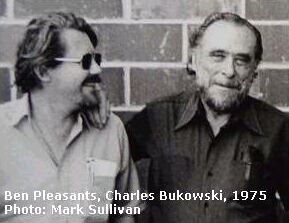

CHARLES BUKOWSKI TAUGHT ME

'HOW TO WRITE A SHORT STORY'

by Ben Pleasants, guest contributor.

[November 7, 2003]

[HollywoodInvestigator.com] Charles Bukowski was a warrior and he used words as a weapon; he loved

literary squabbles. Verbal warfare was his métier and his

typer blazed more brightly when he was on the attack, but only when

the names were changed to protect him from lawsuits. When lawyers

got involved, Charles Bukowski, a celebrated tightwad, withdrew, viewing

an attack on his bank account as life-threatening. [HollywoodInvestigator.com] Charles Bukowski was a warrior and he used words as a weapon; he loved

literary squabbles. Verbal warfare was his métier and his

typer blazed more brightly when he was on the attack, but only when

the names were changed to protect him from lawsuits. When lawyers

got involved, Charles Bukowski, a celebrated tightwad, withdrew, viewing

an attack on his bank account as life-threatening.

In the

late 1970s, as his star began to rise and his bank accounts swelled, Bukowski

sat up in the highest room in his house in San Pedro and looked out on

the harbor at night with all its marine lights and loading cranes and docked

ships, aiming his typer like a 50-caliber machine gun down on all the enemies

of his life: the women who'd betrayed him; the critics and scholars who'd

dismissed him as a "gutter poet," the poets who envied his success; the

bosses who'd fired him; the friends who'd sold him out for a $200 magazine

article; the editors who'd mocked his work; the editors who owed him money;

and every member of his family who ever gave him a minutes' grief. Bukowski was at the top of his game, and the game was King of the Mountain;

now it was time for revenge. As long as he changed the names.

But in

July of 1976, Bukowski was still stuck in Hollywood, sharing conversation

with Sam the Whorehouse man, and I was having my own problems. I'd

named names in print, and if I wasn't hounded by lawyers I was attacked

by what Bukowski called "the lit/crit shitters."

One of

them was Clayton

Eshleman, editor of such solipsistic poetry journals as Caterpillar and Sulfur. On July 20, 1976, Eshleman attacked me in print,

taking me to task for a review I wrote about John Ashbery's poetry volume Self-Portrait

in a Convex Mirror.

I said

of Ashbery's work:

It

is a kind of private meditation that is best kept private, but Ashbery

wants it both ways. He wants our praise and he wants to be left alone

to his sensitive genius, such as it is. It is time to openly flail

such art. A few prestigious poets will praise it (in return for future

praise), a few woeful fossils of magazines like Poetry will find

it "vibrant" or "refreshing expressive," a large enough number of

libraries will dump it out on a dusty shelf after the New York Times

Book Review has done its best to push it along, but ultimately the

work is hollow, hopelessly cut off from the real world, wrapped in conceits. Sadly, Ashbery has written his own little epitaph: "His case inspires interest

but little sympathy; it is smaller than at first appeared."

A

few weeks later Clayton Eshleman struck back. In a letter to the Times Book Review titled "The Cult Lint," he attacked the review

and a poem by Lawrence Ferlinghetti published in the L.A.

Times a few weeks earlier. Eshleman wrote:

Ben

Pleasants' review of John Ashbery's Self-Portrait

in a Convex Mirror (Book Review, July 13) reads like a follow-up on

the Ferlinghetti poem that appeared in the Book Review several weeks previously. Both the Ferlinghetti poem and the Pleasants review mock serious poetry

by asserting that unless poetry is written for "the people" there is something

ridiculous about it.... Pleasants' "voice" is that of a little man

(in the Reichian sense), outside of the central evolving image of poetry

in our time, and bitter about it.... Both the Ferlinghetti poem and

the Pleasants' reviews appear in the Book Review because there is

no serious reviewing policy.... It is a continual shame, an aspect

of failure in Los Angeles for poetry to ever be taken seriously, that Book

Review backs such pot shots.

When

Bukowski read the review and Eshleman's response, he was delighted: literary

warfare in Los Angeles at last! It was like the old Kenyon

Review days from the 1940s. The thought of those old Marxists

who'd attacked Jeffers and Pound and John Crowe Ransom made his eyes fill

with rage.

But what

he told me surprised me. He said I'd finally gotten to where I wanted

to be; I'd made the establishment so mad they wanted me gone. He

said that was really enough; that I'd done my job reviewing poets no one

else reviewed and now it was time to move on. He told me to write

more poetry and begin writing fiction. He said it was time for me

to grow up and listen to my own voice. "Write some short stories. I'll help you send 'em out."

He'd just

received a large check from Hustler and he wanted to celebrate. So he drove his little blue Volks over

to Barney's Beanery for drinks. Strictly on Bukowski! We'd

been there several times, on Santa Monica in West Hollywood. The

food was terrible, but the drinks were large and cold. The customers

were working-class types who spat on the floor, smoked while they drank,

and sprinkled "cunt," "fuck," and "cocksucker" into every line of conversation

they spoke. Bukowski's kind of people.

He always

stopped and pointed out the sign in front: Founded in 1920. "Same

as me," said Bukowski. "Andernach, 1920."

He liked

the other sign even better -- the sign over the bar: NO QUEERS ALLOWED. He'd shout it out like a bad little boy in the first grade who'd just pulled

the panties off a crying six-year-old girl. And just in case you

didn't get the point, he'd quote Steve Richmond's poem "Let the fags have

San Francisco." He wanted me to know where he stood.

* Meat Poetry Society

It

was the perfect hangout for members of the Meat Poetry School. But

I never got it, the macho stuff. I still liked F. Scott Fitzgerald

and Hart Crane; I read Pablo Neruda and H.D. and Galway Kinnell and Emily

Dickinson and Charles Tidler and Marge Piercy. Bukowski yawned at

the thought of them. But he was happy for me; that letter from Eshleman

was like a medal from Kaiser Wilhelm.

"You drew

blood this time," he said over a pitcher of dark beer. He told me

I should put it to work for myself in stories. Like him. He

told me what he was getting from Hustler was real good money, a lot better than The Sparrow or the Free

Press, even if it wasn't steady.

He said

I should write about the women I knew, especially the teachers and nurses

who were living on the edge, caught between ecstasy and hypocrisy; their

sexual habits, their drug usage. He was especially fond of a story

I told him about a woman I'd worked with in a drug hospital who slept with

all the principals on both sides of a labor dispute and, by using her body

as a weapon, broke the strike. I told him I disapproved of what she'd

done. He said I was hopeless. He called me his "Beverly Hills

Anarchist Boswell."

By then I was supposedly writing his biography;

but whenever he sent me to interview a friend it always ended the same

way -- either he owed them money or he'd smashed up all their furniture or

he'd peed on their sofa, or he slept with the wife or girlfriend.

He thought

all people on the West Side lived off their parents' wealth, spent their

evenings in nightclubs, and lived in fear of two things: venereal disease

and drug overdose. He held Steve Richmond up as the prototype of

West Side lifestyle: a rent collector who lived off his father's millions.

I told

him I didn't come from money, I'd been working since I was fifteen, and

I was only a quarter Jewish. He told me being a quarter Jewish was

like being a quarter crazy; it didn't matter if I didn't take it seriously. I told him I didn't. I told him I found it hard to write about women

I knew intimately. He told me I'd get over it. "You have to

be hungry," he said.

He said

if I couldn't write about women who'd fucked me over, I should write about

what I knew: newspaper people, the inside stuff; how much they drank; who

fucked them over; their troubles with money and ego and drugs; their suicides. Did I know any? I said I did. I told him the Gary Mayfield

story, but he said that was too easy; it was already in print.

I

reminded him of the Ramon Navarro story he'd written, about his murder

up on Laurel Canyon. He told me he was hard-up for a column that

week, and besides the story had caused him problems.

He asked

me to tell him the real stuff at the L.A.

Times. We were on our third pitcher of beer and our second bloody

steak. Meat School Poets; only I wasn't one of them.

I said

I once met Otis Chandler in the elevator and he was carrying a fine leather

case. Everyone else stood there not making a sound, but I asked Otis

Chandler what was in the case and he told me a hunting rifle. He

was shooting wild sheep on Catalina Island. I asked if he'd open

the case. He did right there in the elevator, or maybe it was the

lobby. I said it was like a kid playing with his toys.

He asked

if I hated Otis Chandler. I told him he was the best editor the Times

ever had. Bukowski was disappointed. He wanted an Otis Chandler

scandal. I told him he ran over an eighty-year-old lady and they

knocked it right off the news. He told me that wasn't sexy enough. It had to be a blonde in a tight skirt; but I could start with the story

and add the blonde. That was the joy of fiction. I was beginning

to get it. After all that beer I was starting to feel the hunger.

He said

I should take on the big boys, because I was stubborn enough to survive

in a rich man's world; stubborn enough to draw blood. That was true.

So I told

him what I knew. I told him I'd worked as a copy boy at twenty-six

just to get my nails into the concrete enough so the L.A.

Times would publish my stuff. I told him I liked being called

an anarchist, not a Marxist; that it was better than being called a rent

collector behind your back, like Richmond; that nobody owned me. He told me he liked the fact that I could keep up with him, bottle for

bottle, on an all-night bender; that I laughed at myself, at my wife's

infidelities with stock brokers; that I let life hit me in the mouth and

could still see the sadness without giving up. I liked what he said. I still do.

Bukowski

was very careful with writers' truths, but every once in a while he'd hit

me in the face with one, using the Bukowski Zen stick.

He also

said a real writer should have kids. We both had daughters about

the same age. He'd met my daughter once in the living room of my

Beverly Hills apartment, while he spent most of the afternoon looking up

my wife's shorts. My daughter was ten at the time and she seemed

afraid of him.

I'd seen

his daughter, Marina, several times when she was little, playing with crayons

and paper on his beer-soaked carpet. He told me over and over that

whatever money he made from his writing would go to Marina. Money

didn't matter much to him, he said, as long as he had a place to write

and publishers who'd print him and enough money for beer and smokes.

He told me having a daughter gave him a special edge; it allowed him to

see through the eyes of a child. He thought poets who lived for their

work alone -- for art, and had no children -- were cut off from the real world;

the world of love and work and murder and sweat.

He said

that poets were sad creatures but they could be funny. He mentioned

a dozen we both knew, all with no children. He ended with Steve Richmond. He told me he was so tired of the small presses. He laughed about

all the stuff John Martin had asked him to do so he could sell out his "Collector's Copies" for Black Sparrow. He said Martin would ask

him to sign copies of Black Sparrow books in his own snot if he thought

it would make him a buck, but he did it.

Larry

Flynt, on the other hand, asked him for the typed manuscripts, pure and

simple. "There's a guy who understands women," he told me. He told me it was time to "fuck off poetry, let those cunt suckers choke

on the cum of the poet. Write prose. Write stories. Just

give up on poesy [sic] unless you can curse the gods like Jeffers. Or me."

"But how?"

I asked. "How do you break through?"

He thought

back to when he was a kid of twenty, sitting on a park bench, running away

from World War Two. He told me he'd been reading Kenyon

Review and Sewanee,

which he pronounced as it was spelled, not as it's sung in the song "Way

Down Upon..." And he was surprised it was the same word.

So

we talked about critics. The New Critics. He said that the

poetry he read on that park bench in Texas was stilted and dead, without

any feeling, so different from Jeffers who always thrilled him; but the

critical articles were bristling with anger, frustration, and hatred.

"These

guys were so neatly bitchy in such a high intellectual, vicious way. The way they used the language in those critical articles was on a far

higher level than all their creative work." He told me to forget

about Eshleman, to laugh off the viciousness of a minor leaguer. "It doesn't count for anything."

Bukowski

told me that poets have only that little bit of turf to quarrel about. "Nobody reads them. They read each other. They hate me because

my poetry sells; because I connect with the real world and guys like Eshleman

and Ashbery connect with no one." He told me they were born dead

and could only exist through viciousness. "Just cool off and get

the fuck off the poetry train. Write straight fiction. Write

a play. Anything but poetry."

I had another beer and considered

his words. I felt better already. That was the third time Bukowski

told me to read Dan Fante. Fante would help

me find the way just as he'd lit up Bukowski.

Bukowski

showed me a story he'd written and sent out to Hustler. "These guys publish real stuff. Send them something. And they

pay real money." On the table was a check for $1,200. He told

me to forget about guys like Eshleman. "They always fuck up. It's just ego. You'll see." And then we got down to writing

short stories, holding the line, hammering it home.

I asked

him how he got started with the short story. He told me when he was

in his twenties he was turning out five stories a week. "They were

lyrical. They were rambling. The plot and content were secondary. It was a vomiting up, an effusion of feeling." The rejection slips

told him he should write poetry. "I didn't think much of poetry. I thought I was really cutting loose with this new form, like a Mahler

symphony."

When he

started writing stories in 1940, he told me he was looking for something;

looking for a mentor, so he headed east on his way to Florida to find Ernest

Hemingway. "I made it to Miami and then I ran out of money," he said. He got stuck with the same dead-end jobs he always had and continued batting

out stories until he hocked his typewriter in Philadelphia and couldn't

afford to get it back. "That's all in the new book, Factotum."

I asked

if he'd read Dan Fante by then. He told

me he'd read him when he was nineteen or twenty, but Fante's method of

vivid writing and short chapters was hard for him to imitate.

Only when

he ran into D.H. Lawrence's The

Prussian Officer did he get it. "It's about ultimate human cruelty,"

he told me. "There's a tightness of line." He recalled his

earliest stories, the ones he'd hand-printed and sent out, always about

the same thing: "People mentally fucked up and unhappy, not knowing what

to do, how to get out of bed, how to get a job, how not to get a job, how

to get through another day."

He recalled

working at a job at Coronado Parts Warehouse on Flower and 17th Street. "The job was easy and the boss was not too bad." He went home and

wrote "Twenty Tanks From Kasseldown," which was accepted for publication

by Black Sun Press in 1946. Henry Miller was the prose editor, but

Bukowski didn't like the story. He was learning.

Then he wrote

a story for a small magazine titled Matrix. It was about a

baseball player who'd been playing baseball "for quite a while. One

day he's standing in the outfield. He's been doing some thinking. The baseball came to him and he just didn't want to catch it. He

just stood there. He didn't care. I think it was a pretty good

story," he told me, "but I think I could write it better now."

I asked

if he'd like it republished. He said no. He was still learning

then. He didn't quite have it. Not the way Fante did. Drinking and working tired him out. "I don't think I had so much

energy in those days. I didn't put as much into each story. I just pushed them out. I didn't keep carbons. I'm a little

bit calmer now. It gives me a chance to put more feeling.... I don't want to say false feeling, that can happen, too." He knew

he was getting there. He put in the time but the stories weren't

jumping off the page.

He recalled

writing another story called "The Itch To Scribble." But he told

me he still didn't have it. He said he was learning how not to write

a short story. What he needed was to learn about THE FEMALE.

* Bukowski's Battle of the

Sexes

He was

between women at the time and laughing a lot about his busted relationships. He told me how Lisa Williams tried to hold onto him by taking pills; by

trying to overdose. "I had to reach down her throat and she had these

false teeth. I pulled out the teeth." He was laughing. The blood, the pills, the vomit, the false teeth. "You need those

smoking hot cunts that drive you crazy, that keep you up all night smoking

and drinking and screaming at the moon. That's when you learn...but

first let me tell you how not to write a short story."

He talked

about all the early work that had disappeared into the trash. "They

were full of complaints. I wanted too much too fast, and I was weeping

in the wind. The unrecognized artist shit. 'THE WORLD SHOULD

KNOW THAT I HAVE THIS GIFT.' "

We finished

our beer and drove back to his place on Carlton Way. He made a few

comments about my wife. Was she fucking someone? I told him

about the stockbroker.

"Yeah,"

he said. "Not good." He told me to handle it, to use it, to

get it down. "Write about the two of them," he told me. "Think

about it till it drives you crazy, then get it down." That, he said,

is what he learned from Fante; the war between men and women -- it had

to be real. "Camilla was no made up cunt," he said. She was

still out there somewhere.

He asked

what I was working on. I told him about a story I was writing about

Vietnam. He turned up his nose. It was after 2:00 a.m. We drank more beer and there was a knock on the door. It was Cupcakes

and her friend, Georgia. Cupcakes needed some money.

Cupcakes,

Bukowski told me, had been Miss Pussycat Theatre a few years back. She was the kind of women who drove him crazy and moved him to his typer. Georgia was the ugliest woman I ever met. Cupcakes grabbed a twenty,

then split with Georgia. Bukowski said they were headed to the Time

Motel. He liked the name. He said his neighbor, Sam the

Whorehouse Man, worked there at night. They were all in his stories,

he told me.

That was the way it worked. You needed materials

you could work with, even if they looked like Georgia and Sam and Neeli

Cherry (later Cherkovski), with that tic of his that twisted his head around

whenever he got flustered. The dregs, he said, just like the people

in Celine; but they had to be fictionalized.

Cupcakes

went off, wobbling on her high heels, smoking a cigarette. Bukowski

waved at her through the window. "See, that's what you need. A woman like that."

"How about

Jane?"

"Jane

was worse." He told me about Jane. About Jane and Baldy and

about Jane and all the other guys he'd caught her with. He asked

me if I ever caught my wife in bed with another man. I told him one

day I came home early from work, and she was lying in the bed stark naked

when she should have been at work, but I never found the guy. He

laughed.

I told Bukowski he probably climbed out the window. He remembered the apartment on Doheny. It was on the second floor. He laughed. "Maybe he broke his back." He told me I should

use that, but make it ten times worse; first drink some beer and then get

it all down like a blues singer crying about his lost love, but make it

funny; that was the thing.

"Use pain,"

he said. "Let it all in." He told me when he was struggling

writing stories it just got worse and worse. He had to stop. He had to take in all the pain and let it settle like grounds in bitter

coffee. He said he got up one day and threw all his stories away

settling down to drinking. He really didn't care then whether he

lived or died. He lived on a candy bar a day.

I'd heard this

story many times; how he'd hocked his typer in Philly and started over

with his stories. He told me he learned to print faster than he could

type and sent out his new stories to magazines like Harpers, The

Atlantic, and Story. "Story was the only one that

responded. The others, you know, would say, 'This nut again who hand-prints his stories. Ah ha ha ha.' Maybe they didn't even read

them.”

He told

me it was women who make men write. He knew that woman, Camilla,

had really put her hooks in Dan Fante. He

told me to look for a woman who was really hot but not too smart, like

Cupcakes. I told him I had my eye on a few. He wanted to know

who. I said Kate Braverman was one of the most beautiful and exciting

women I'd met.

Bukowski

was aware of her. He'd read her work, but he told me she was too

smart, and she was Jewish. Jewish women always put him off. He told me a woman like Kate Braverman could really make a man crazy, but

he thought she'd pack it all away in her own poetry and the fiction. I argued it was possible for two people to take away materials from one

experience. He told me I'd be better off writing about my wife's

infidelities. "Just write real stuff."

I decided

to try out his suggestions. I gave up writing poetry reviews. I walked across town and got myself a job at the Free Press as Special

Arts Editor. I checked out Braverman, followed her around for a while

and began poetry readings at the Alley Cat. And I wrote a few stories. One was for Hustler. They bought

it and I showed Bukowski the art work. He was surprised. It

wasn't what he'd told me to write. Where was the stockbroker?

* Kate Braverman

I took Braverman on a date. She wanted some dream candy, but I wasn't

a user. She told me she'd thrown away her "works." Could I

get her some? I called a friend who'd been a user of heroin, but

she was now on methadone and no longer injected herself.

I told

Braverman that Bukowski had read her poetry and liked it. I told

her what he'd said about a few of her poems: "She writes like a man." |

Kate

Braverman; Lithium

for Medea book cover.

|

She was flattered. She asked me if I used drugs. I told her

about Steve Richmond and Tim Buckley and Jim Morrison, who I'd met at UCLA,

and how drugs scared me. I suggested she give up the coke she was

shooting into her ass and try some red wine. She said she'd been

on a diet.

She pulled

up her peasant blouse and showed me her belly. She was hot, sensual,

dusky. We talked about her father; how he was old and sick and nobody

looked after him. She said he used to hang out at the Hollywood Roosevelt

Hotel, sitting out by the pool for just the price of a cup of coffee or

a soda, but they kicked all the old-timers out. He had no place to

go but his seedy room, while her mother, Millicent, lived in a luxury house

in Beverly Hills.

She told me about all her boyfriends at Venice

High School; how they were innocent and how she was not. She remembered

all their names and how her parents had to struggle to survive. She

insisted we play a game of Scrabble, which she won by two points. She talked about how she wanted to be a mother. She asked me about

my wife and my job. I told her I had to work in the morning.

I told

her she should give up her dream candy and stick to liquor like Bukowski

and me. She told me she could handle her drugs; they were useful

in her writing. She was writing about people she knew, and more than

half the people she knew were on drugs. We walked across the street

to an Italian restaurant in her neighborhood, Echo Park. We drank

a lot of red wine. We both got very drunk. We talked about

France and Venice and South America. We drank two bottles of red

wine.

When we

left the restaurant she lay down on the roadway with cars coming in every

direction. I had to drag her to her feet and carry her across the

road and up the hill to her home. She told me she was feeling a little

numb; when we got to her house she rushed into the bathroom and threw up

all the Italian food. I held her up as she vomited into the can,

and she gave me a very sad look. We were staring into the bathroom

mirror.

"Baby

don't look too good," she said, stripping off her clothes. Vomit

trailed down her chin onto her breasts, but to me she still looked beautiful;

those sad, lonely dark eyes, so much like a gypsy, her wild dark hair,

that soft mouth of hers that could use words like a razor, and her pale,

taut body. I wiped her off but she pushed me away. The night

air and what she'd flushed down the toilet reduced her drunkenness. She told me she didn't think wine would work for her. Then she made

me a cup of coffee, but I was still very drunk.

She called

my wife and told her I was too drunk to drive home. Then she put

me on the couch, covered me up with a blanket, and kissed me goodnight,

more like a mother than a lover. When I woke in the morning she gave

me breakfast and checked to see if I was okay. I reminded her that

she was the one who vomited up her dinner. Then she called my principal

and told her I'd not be in that morning. She was very efficient.

When I

told Bukowski about my date with Kate Braverman, he made some comments

about living up to the motto of the Meat School, like Richmond. I

told him the last time I'd seen Richmond he was suffering through his fifth

round of the clap. Bukowski wasn't satisfied. The Meat School

of Poets was engaged in an all-out war with The Female, and once again

I was on the losing side.

He wanted to know more. How did her

breath taste? Did I get a look at her clit? He asked me to

describe her body. I told him I was pretty drunk and with her hair

falling over one eye she reminded me of a young woman I'd known at UCLA. The one who looked like Anouk Aimee. He told me I'd read too much

Fitzgerald.

"How about

her nipples?" he asked.

"Which

one?"

"Both."

He was

talking about nipples and I was talking about Braverman and Anouk Aimee. I told him the girl who looked like Anouk Aimee had large breasts and tiny

nipples. He only wanted to know about Kate Braverman. I said

Braverman's breasts were large, but they drooped downward like two large

pendants and I couldn't remember if I'd seen her nipples at all.

"Maybe

she didn't have any," he said.

Then he told me about a woman who

worked at the downtown library who'd wear low-cut sweaters, and you could

see her whole breast when she bent down, only she had no nipples -- none

at all. I told him I thought Kate Braverman had nipples, I just couldn't

remember what they looked like. Then I drove home and started to

write stories.

Sometime

later Kate called me back. She asked if I'd do a reading with her

at the George Sands Book Store in Westwood. "I'll give you head right

out in front of the audience," she said. We'd read in tandem, just

the two of us. She suggested we read all our Europe poems, after

she gave me head.

I thought

she was kidding.

The reading

took place in the late 1970s. Kate and I read poems about Europe,

and she did threaten to give me oral sex in front of the audience but I

declined. My friend Kenneth Achitity introduced us. We traded

quips back and forth and read from published and unpublished works.

* Poet's War With Clayton Eshelman

When

the reading was over I spoke with the owner, Charlotte Gusay. She

had a question for me: Did I know Clayton Eshleman? I laughed and

told her no, I'd never met him. She had a letter to show me written

by Clayton. It was about Charles Bukowski. Charlotte had written

Eshleman to ask about Charles Bukowski. Would he be a good reader?

Eshleman thought not. Bukowski was unpredictable, he said. He could be violent. He was boorish and crude. Eshleman neglected

to mention that Bukowski was getting from $500 to $1,000 up front for each

reading and the rooms were always packed.

I was

amused. Bukowski and Eshleman had the same publisher. I asked

Charlotte if I could photocopy the letter. I told her I was Bukowski's

authorized biographer. That was true at that time. She gave

me the letter. I called Bukowski and read what Eshleman had written. I thought it would give him a laugh.

It didn't. He was angry. He wanted a copy of the letter. Over and over he'd told me he was

the locomotive pulling the Black Sparrow train. "I have to deal with

these cocksuckers cutting my balls off behind my back." I took him

a copy of the letter and handed it over personally. He bought me

three pitchers of beer.

A few

weeks later Bukowski was brimming over with joy. He told me Eshleman

had been John Martin's house guest for the weekend. "Martin asked

him when he got there if he'd been saying anything about me. Cursing

me out. Eshleman denied it. Then he asked him again at dinner."

Bukowski was smiling. He loved stories like this.

"John

asked him the same question a few more times. 'Have you been saying

anything bad about Bukowski?' Clayton said, 'No.' He loved

Bukowski. Bukowski was great. And then he showed him the letter

to Charlotte Gusay, owner of the George Sand Book Store."

By this

time Bukowski's voice

was animated. He told me Eshleman just stood

there stunned. He didn't know what to say. He was caught in

a flat-footed lie. Bukowski laughed his evil laugh. Ah Ha Ha

Ha Ha Ha. He'd finally caught one of his backstabbers with his pants

down. He reminded me about the letter Eshleman had written to the

Times, The Cult Lint.

"See," he said, "what did I tell you?"

A short

time later I heard from Charlotte. She wasn't too pleased, but she

did see the humor in the situation. Eshleman had called her. He was furious. She'd given him my number. Then Eshleman called

me. He could hardly contain his rage. Why did I give his letter

to Bukowski?

I told him I didn't. I gave him a copy. He could read between the lines. All those poetry wars were still

going on in Eshleman's little head, but for me events were merely comical. I laughed in his face and reminded him about his attack on Ferlinghetti. He was irate and he wanted his letter back.

It was

1979. I'd returned from France a week early; my wife was with a new

boyfriend off S.F. on the island of Tiburon. The word means shark

in Spanish. She was there with a lowly clerk and his brother from

the same brokerage house she worked for in Los Angeles. My daughter

was at home and gave me the number in Tiburon.

Shortly after, my

wife filed for divorce. At first I was angry and then I was glad. The clothes were all over the place, and in the middle of the adventure

the house was robbed, but I was smiling.

I told

Bukowski the latest about my wife. He said it was good I didn't catch

the two brothers in my own bed. He knew I collected rifles. "Now you have a novel," he told me.

I told

him I'd rather write short stories. He said to "Beware of overabundance;

too many lines. The unsaid things can be much more powerful than

the said." He told me not to feel sorry for myself. I said

I just felt sorry for my daughter; she was in the middle.

Since

I had him on a subject he never talked about, I asked WHO Bukowski wrote

for. He told me "D.H. Lawrence said 'Art for my sake.' Let's

just say I'm getting the poison out. It helps me survive."

But we

were both still laughing about Clayton Eshleman.

It still

makes me smile when I think of the expression Eshleman must have had on

his face when John Martin read that letter.

As for

Kate Braverman, she kicked her drug habit, went on to write two fine novels

and several volumes of poetry. I did an interview with her for the L.A. Times about poetry, of course,

when she was thinking about having a baby. I met the guy.

His

name was Pedro something. They never married but she had a lovely

daughter like me and Bukowski. I was glad for her. She was

still very beautiful and she still wrote like a man, but as Bukowski told

me, she was too smart for me and too Jewish.

Hustler published my first commercial story in their July 1978 issue: "Even the

Kings in Their Winter Palaces," a story about a Vietnamese father who carried

the head of his dead son from Quang Tri to Hue. Bukowski thought

it was a good story and it all turned out okay.

Copyright 2003 by Ben Pleasants.

|