|

Home

About

Us

Bookstore

Links

Merchandise

Forum

Guest

Book

Blog

Archive

Books

Cinema

Fine Arts

Horror

Media & Copyright

Music

Public Square

Television

Theater

War & Peace

Affilates

Horror Film Aesthetics

Horror Film Festivals

Horror Film Reviews

Tabloid Witch Awards

Weekly Universe

Archives

|

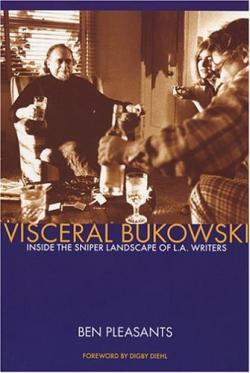

BEN PLEASANTS'S VISCERAL BUKOWSKI

by Digby Diehl. [November 17,

2004]

[HollywoodInvestigator.com]

Ben Pleasants and I both came to UCLA in the fall of 1964. He, two

years out of Hofstra in New York; I, two years out of Rutgers in New Jersey. As young men who shared a passion for writing and the arts, we met through

the campus newspaper’s arts section, Intro. Established six

years

earlier, the weekly supplement was a remarkable hotbed of talent, which

included writers Laurence

Goldstein, Larry

Dietz, Burt

Prelutsky, Joel

Siegel, Norman Hartweg, Harry

Shearer, Lewis

Segal, and artist Hank

Hinton. [HollywoodInvestigator.com]

Ben Pleasants and I both came to UCLA in the fall of 1964. He, two

years out of Hofstra in New York; I, two years out of Rutgers in New Jersey. As young men who shared a passion for writing and the arts, we met through

the campus newspaper’s arts section, Intro. Established six

years

earlier, the weekly supplement was a remarkable hotbed of talent, which

included writers Laurence

Goldstein, Larry

Dietz, Burt

Prelutsky, Joel

Siegel, Norman Hartweg, Harry

Shearer, Lewis

Segal, and artist Hank

Hinton.

Ben and I shared many parallels in our careers: we both

were involved with UCLA campus publications that caused censorship scandals;

we both wrote theater reviews as stringers for the Los

Angeles Times; we both were energetic contributors to the Los Angeles

Free Press; and, although our careers have diverged, we both have continued

to write throughout our lives.

In Visceral

Bukowski, Ben begins by evoking memories of Los Angeles in the 1960s

with a vividness and joyous abandon that sweeps me back into an era I recall

with considerable happiness. His descriptions of Westwood, the political

energy, the libraries, the Daily

Bruin,

and the campus in general are wonderfully evocative, as are his delightfully

candid memories of youthful love affairs.

When we began as stringers

for the Times, it was very much a

writer’s newspaper, and the freedom allowed even to young non-staff contributors

was considerable. Under publisher Otis Chandler’s watchful eye, the Times nurtured good writing, and

some true giants of journalism -- including Jack Smith, Jim Murray, Robert

Kirsch, and Charles Champlin -- taught by example in every edition.

Ben generously credits me

with being the first book editor to run his reviews of Charles Bukowski,

and I am sure he is correct, if only because I know that my predecessor

and

mentor at the Times, Robert Kirsch,

disliked Bukowski’s writing. What Ben may not have known until he

read these words is that I shared Kirsch’s view. My support of Ben

and of his Bukowski reviews did not emerge from any liberal sentiments

or spirit of friendship. They emerged from two precepts I developed

early in my editorship.

First, as I regularly read

reviews from publications all over the country, I was appalled to see that

then -- as now -- the great majority of book editors and book reviewers focused

almost exclusively on that great Mecca of book publishing, New York City. In those days, the Los Angeles Times was the most important journalistic voice of the West and I determined

that its book section should be a voice for the literature of the West. It seemed only reasonable that local authors could expect a review (not

necessarily a positive review) in their hometown newspaper.

Second,

I learned from some of my own Times editors – including Jim Bellows, Jean Sharley Taylor, and Charles Champlin -- that an editor does not have to agree with all of his or her writers. An editor has to have confidence in a writer’s ability to argue the merits

of a point-of-view with skill and intelligence. I had confidence

in Ben, and he never disappointed me.

This remarkable dual memoir

does not disappoint either. The "Beverly Hills Anarchist" (Ben) and

the "Dirty Old Man" (Buk) both come to life through a series of rambling

conversations, comic adventures, and stories that are insightful and entertaining. Ben decided to be Bukowski’s official biographer early in their friendship,

and Bukowski opened up his life to Ben with typical raucous candor. With equal openness, Ben reports their long nights of smoking cigars, drinking

and trading stories about writers for

stories about women.

Despite numerous comical

refusals from Bukowski’s ex-wives, old girlfriends, and former companions,

Ben persisted in locating people who knew Buk in most phases of his life. Here is Ben’s description: "…Whenever he sent me to interview a friend

it always ended up the same way – either he owed them money or he’d smashed

up all their furniture or he’d peed on their sofa, or he slept with the

wife or girlfriend."

I was fascinated by Ben’s

techniques of interviewing people Bukowski had offended and by his tenacity

in pursuing every possible biographical lead. The sexism, Nazism,

the drunkenness, the cruelties – it is all here, unflinchingly described

-- but always with sympathy for the man. As their unlikely friendship

unfolds in these pages, Ben is frank about why he is attracted to Buk’s

sense of freedom, his reckless audacity, his refusal to take the safe or

easy route. You may be shocked or disgusted by some passages, but

you definitely come away knowing Bukowski, in all his glory.

On the other hand, Ben has

always had a professorial look, a gentlemanly manner that makes the radicalism

of his thinking particularly amazing. He portrays himself in this

book with the same forthright assessments as he portrays his biographical

subject.

Perhaps all biographers should be this open, because his

admiration for Buk is infectious. In the end, Ben has done more than

a Boswellian job. He has told the intertwined stories of two different

men’s lives effectively and engagingly. Moreover, he has made Bukowski

and Bukowski’s bizarre philosophy of life come alive so vividly that these

revelations may illuminate the man’s work.

If, after finishing Visceral

Bukowski, each reader is prepared -- as I am -- to reread Bukowski’s

work with a fresh understanding, then Ben, Buk’s friend and literary biographer,

has done his job well.

|